In this blog post I help app developers to understand the terminology of a Swift Package and how to integrate a more complex structured Swift Package in an iOS application.

The simplest package structure, created by the swift package init command, consists of

- a package

- with a single product (type: library)

- using a single target (+ a test target)

- with a single product (type: library)

The names of all those package/product/target is identical.

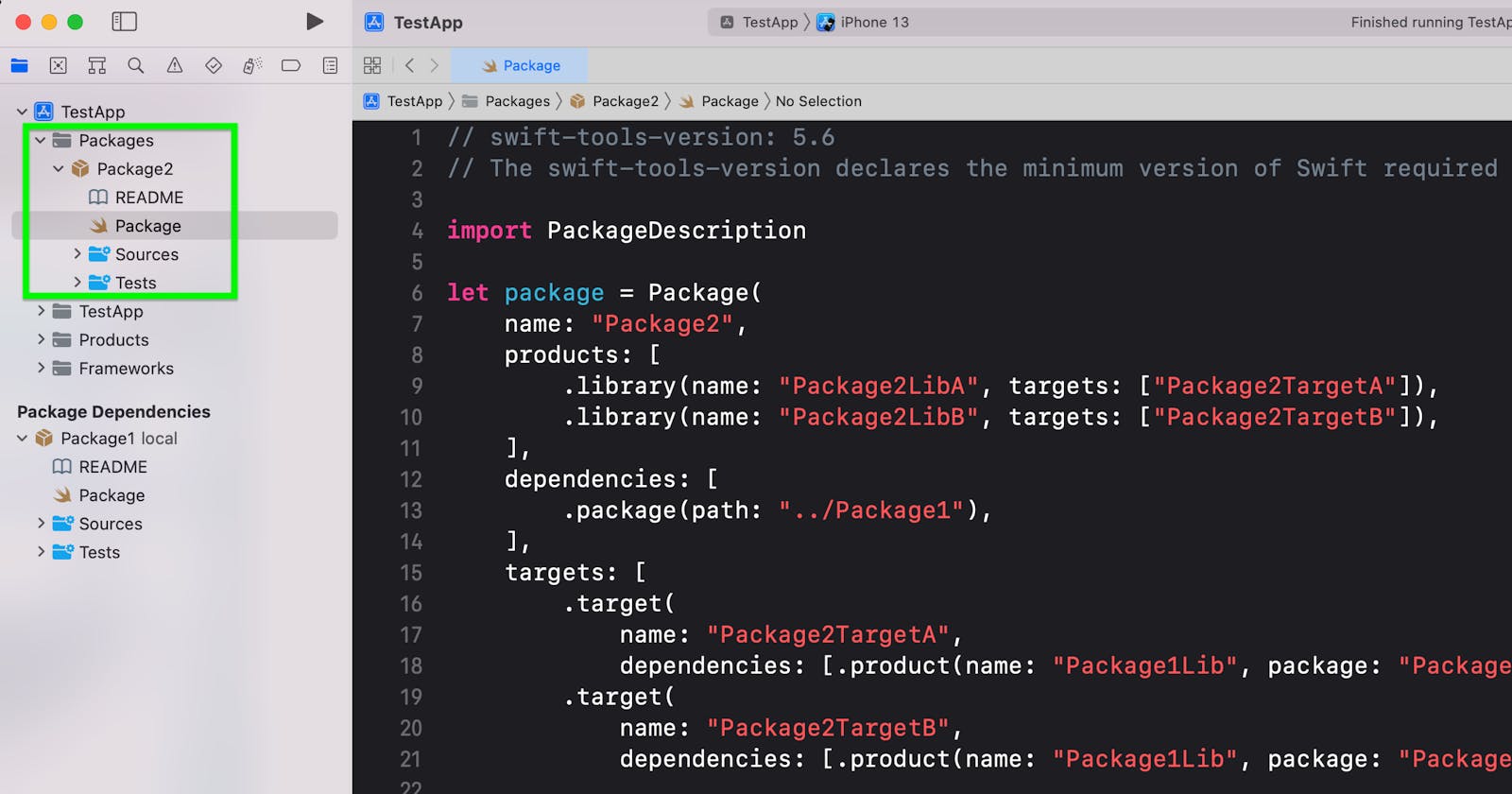

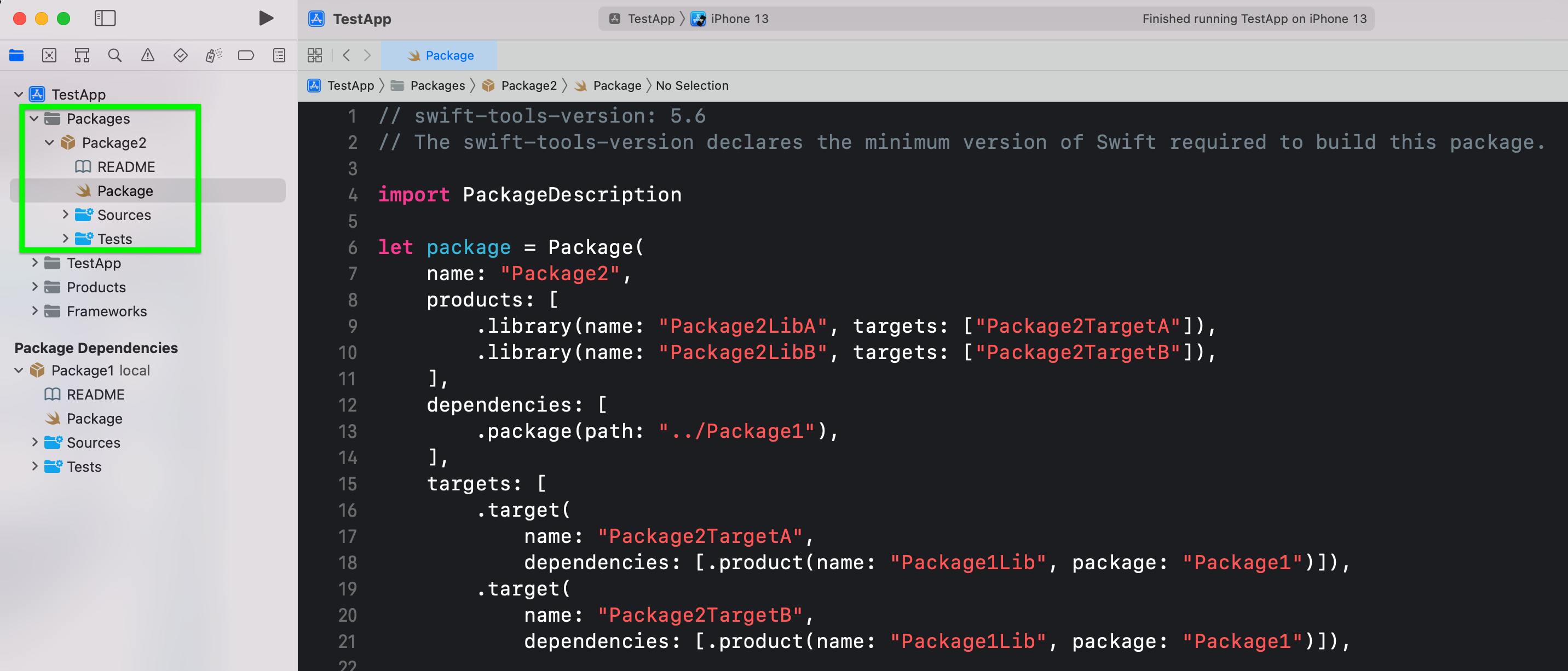

Let's look at a more complex example:

// swift-tools-version: 5.6

import PackageDescription

let package = Package(

name: "Package2",

products: [

.library(name: "Package2LibA", targets: ["Package2TargetA"]),

.library(name: "Package2LibB", targets: ["Package2TargetB"]),

],

dependencies: [

.package(path: "../Package1"),

],

targets: [

.target(

name: "Package2TargetA",

dependencies: [.product(name: "Package1Lib", package: "Package1")]),

.target(

name: "Package2TargetB",

dependencies: [.product(name: "Package1Lib", package: "Package1")])

)

]

)

This package (named Package2 here) offers two library products. Each product has its own target. Each target makes use of a library offered by a package dependency.

Let me start explaining the different building blocks from the view of an app developer.

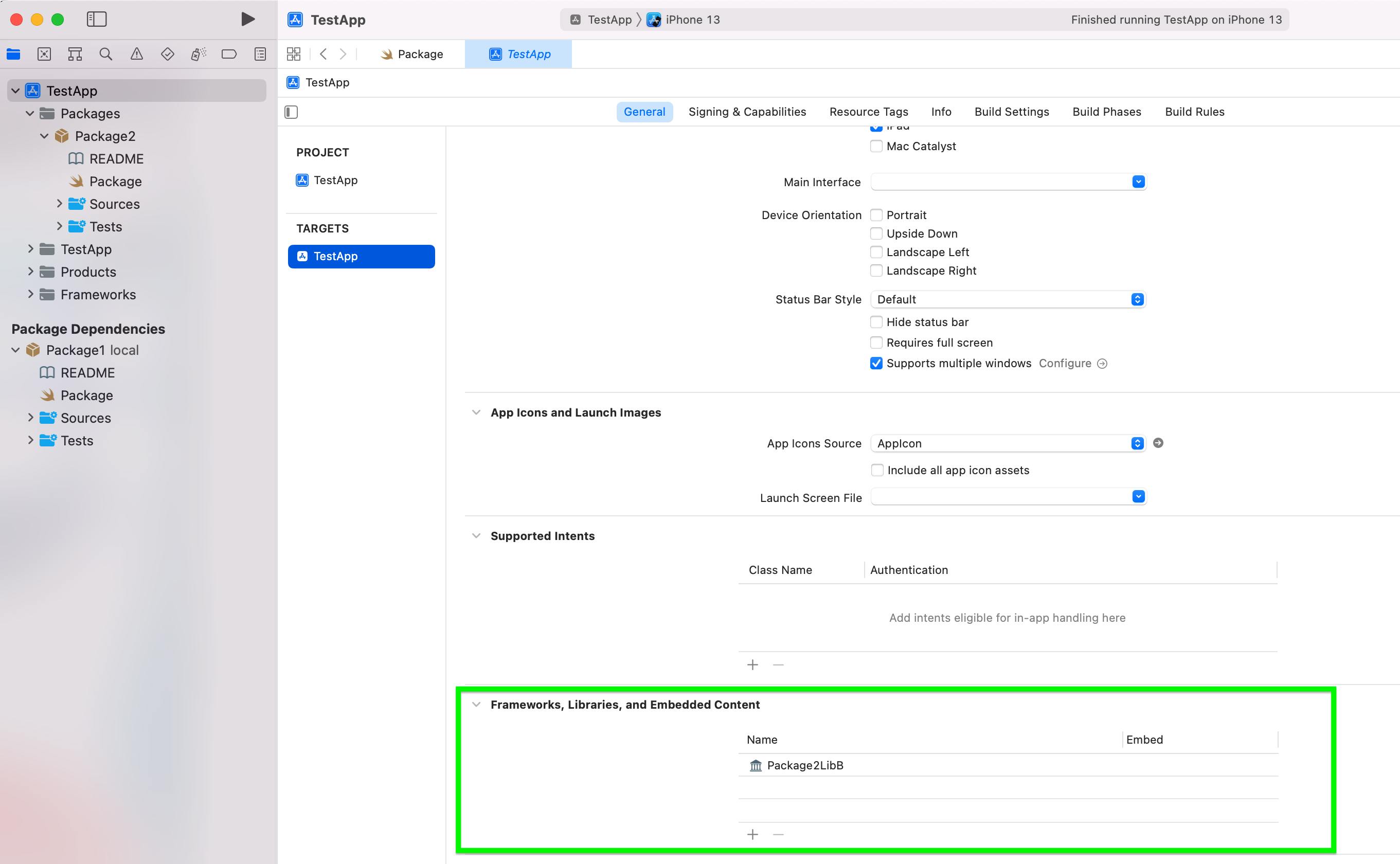

- You want to use functionality from a package => you add the package to your Xcode project.

You want to use a library => you add a library product to your app target in Xcode.

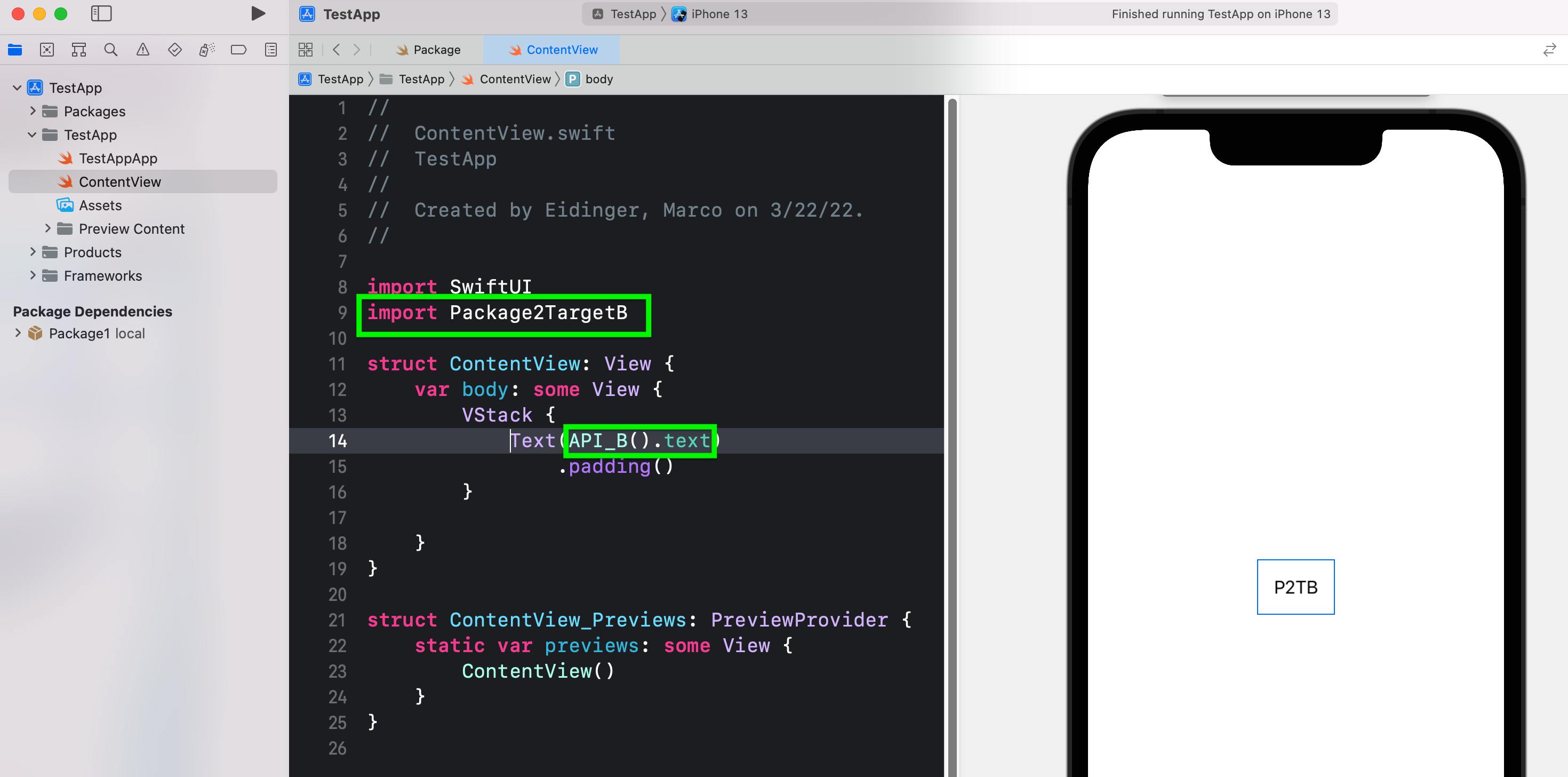

Finally, when importing related code from the library => you are using the

import <target/module>statement.

In this example the module

Package2TargetBoffers a public structAPI_B.

A Swift target is pretty much equal to a Swift module, so they are often used interchangeably. A module specifies a namespace and enforces access controls on which parts of that code can be used outside of the module.

I highly recommend reading the definition given by Jeremy David Giesbrecht in the Swift Forum. It speaks more to package developers.